Potentiometer

| Potentiometer | |

|---|---|

A typical single-turn potentiometer |

|

| Type | Passive |

| Electronic symbol | |

| (International) (US) |

|

A potentiometer ( /pɵˌtɛnʃiˈɒmɨtər/), informally, a pot, is a three-terminal resistor with a sliding contact that forms an adjustable voltage divider.[1] If only two terminals are used (one side and the wiper), it acts as a variable resistor or rheostat. Potentiometers are commonly used to control electrical devices such as volume controls on audio equipment. Potentiometers operated by a mechanism can be used as position transducers, for example, in a joystick.

Potentiometers are rarely used to directly control significant power (more than a watt), since the power dissipated in the potentiometer would be comparable to the power in the controlled load (see infinite switch). Instead they are used to adjust the level of analog signals (e.g. volume controls on audio equipment), and as control inputs for electronic circuits. For example, a light dimmer uses a potentiometer to control the switching of a TRIAC and so indirectly to control the brightness of lamps.

Contents |

Potentiometer construction

A potentiometer is constructed with a resistive element formed into an arc of a circle, and a sliding contact (wiper) travelling over that arc. The resistive element, with a terminal at one or both ends, is flat or angled, and is commonly made of graphite, although other materials may be used. The wiper is connected through another sliding contact to another terminal. On panel potentiometers, the wiper is usually the center terminal of three. For single-turn potentiometers, this wiper typically travels just under one revolution around the contact. "Multiturn" potentiometers are usually constructed of a conventional resistive element wiped through a worm gear, although other types exist with a helical resistive element and a wiper that turns through 10, 20, or more complete revolutions. Besides graphite, materials used to make the resistive element include resistance wire, carbon particles in plastic, and a ceramic/metal mixture called cermet.

A string potentiometer is a multi-turn potentiometer operated by an attached reel of wire turning against a spring, enabling it to convert linear position to a variable resistance.

In a linear slider potentiometer, a sliding control is provided instead of a dial control. The resistive element is a rectangular strip, not semi-circular as in a rotary potentiometer. Due to the large opening slot for the wiper, this type of potentiometer has a greater potential for getting contaminated.

Conductive track potentiometers use conductive polymer resistor pastes that contain hard-wearing resins and polymers, solvents, lubricant and carbon – the constituent that provides the conductive properties. The tracks are made by screen printing the paste onto a paper-based phenolic substrate and then curing it in an oven. The curing process removes all solvents and allows the conductive polymer to polymerize and cross-link. This produces a durable track with stable electrical resistance throughout its working life.

Laws or tapers

Potentiometers can be obtained with either linear or logarithmic relations between the slider position and the resistance (potentiometer laws or "tapers"). A letter code ("A" taper, "B" taper, etc.) may be used to identify which taper is used, but the letter code definitions are variable over time and between manufacturers.

Linear taper potentiometer

A linear taper potentiometer has a resistive element of constant cross-section, resulting in a device where the resistance between the contact (wiper) and one end terminal is proportional to the distance between them. Linear describes the electrical characteristic of the device, not the geometry of the resistive element. Linear taper potentiometers are used when an approximately proportional relation is desired between shaft rotation (or slider position) and the division ratio of the potentiometer; for example, controls used for adjusting the centering of (an analog) cathode-ray oscilloscope.

Logarithmic potentiometer

A logarithmic taper potentiometer has a resistive element that either 'tapers' in from one end to the other, or is made from a material whose resistivity varies from one end to the other. This results in a device where output voltage is a logarithmic function of the mechanical angle of the potentiometer.

Most (cheaper) "log" potentiometers are actually not logarithmic, but use two regions of different resistance (but constant resistivity) to approximate a logarithmic law. A logarithmic potentiometer can also be simulated (not very accurately) with a linear one and an external resistor. True logarithmic potentiometers are significantly more expensive.

Logarithmic taper potentiometers are often used in connection with audio amplifiers as human perception of audio volume is logarithmic.

Rheostat

The most common way to vary the resistance in a circuit is to use a rheostat,[2] a two-terminal variable resistor. Rheostats are usually designed to handle much higher voltage, current and power than potentiometers. Typically they are constructed as a resistive wire wrapped to form a toroidal coil with the wiper moving over the upper surface of the toroid, sliding from one turn of the wire to the next. Sometimes a rheostat is made from resistance wire wound on a heat-resisting cylinder, with the slider made from a number of metal fingers that grip lightly onto a small portion of the turns of resistance wire. The "fingers" can be moved along the coil of resistance wire by a sliding knob thus changing the "tapping" point. They are usually used as variable resistors rather than variable potential dividers.

Any three-terminal potentiometer can be used as a two-terminal variable resistor by leaving one of the end terminals disconnected. However, it is common practice to connect the wiper terminal to the unused end of the resistance track to reduce the amount of resistance variation caused by dirt on the track.

Digital potentiometer

A digital potentiometer is an electronic component that mimics the functions of analog potentiometers. Through digital input signals, the resistance between two terminals can be adjusted, just as in an analog potentiometer.

Membrane Potentiometer

A membrane potentiometer uses a conductive membrane that is deformed by a sliding element to contact a resistor voltage divider. Linearity can range from 0.5% to 5% depending on the material, design and manufacturing process. The repeat accuracy is typically between 0.1mm and 1.0mm with a theoretically infinite resolution. The service life of these types of potentiometers is typically 1 million to 20 million cycles depending on the materials used during manufacturing and the actuation method; contact and contactless (magnetic) methods are available. Many different material variations are available such as PET(foil), FR4, and Kapton. Membrane potentiometer manuafacturers offer linear, rotary, and application-specific variations. The linear versions can range from 9mm to 1000mm in length and the rotary versions range from 0° to 360°(multi-turn), with each having a height of 0.5mm. Membrane potentiometers can be used for position sensing.[3]

Potentiometer applications

Potentiometers are widely used as user controls, and may control a very wide variety of equipment functions. The widespread use of potentiometers in consumer electronics declined in the 1990s, with digital controls now more common. However they remain in many applications, such as volume controls and as position sensors.

Audio control

One of the most common uses for modern low-power potentiometers is as audio control devices. Both linear potentiometers and rotary potentiometers are regularly used to adjust loudness, frequency attenuation and other characteristics of audio signals.

The 'log pot' is used as the volume control in audio amplifiers, where it is also called an "audio taper pot", because the amplitude response of the human ear is also logarithmic. It ensures that, on a volume control marked 0 to 10, for example, a setting of 5 sounds half as loud as a setting of 10. There is also an anti-log pot or reverse audio taper which is simply the reverse of a logarithmic potentiometer. It is almost always used in a ganged configuration with a logarithmic potentiometer, for instance, in an audio balance control.

Potentiometers used in combination with filter networks act as tone controls or equalizers.

Television

Potentiometers were formerly used to control picture brightness, contrast, and color response. A potentiometer was often used to adjust "vertical hold", which affected the synchronization between the receiver's internal sweep circuit (sometimes a multivibrator) and the received picture signal, along with other things such as audio-video carrier offset, tuning frequency (for push-button sets) and so on.

Transducers

Potentiometers are also very widely used as a part of displacement transducers because of the simplicity of construction and because they can give a large output signal.

Computation

In analog computers, high precision potentiometers are used to scale intermediate results by desired constant factors, or to set initial conditions for a calculation. A motor-driven potentiometer may be used as a function generator, using a non-linear resistance card to supply approximations to trigonometric functions. For example, the shaft rotation might represent an angle, and the voltage division ratio can be made proportional to the cosine of the angle.

Theory of operation

The potentiometer can be used as a voltage divider to obtain a manually adjustable output voltage at the slider (wiper) from a fixed input voltage applied across the two ends of the potentiometer. This is the most common use of them.

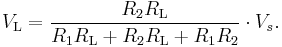

The voltage across  can be calculated by:

can be calculated by:

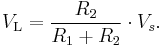

If  is large compared to the other resistances (like the input to an operational amplifier), the output voltage can be approximated by the simpler equation:

is large compared to the other resistances (like the input to an operational amplifier), the output voltage can be approximated by the simpler equation:

(dividing throughout by  and cancelling terms with

and cancelling terms with  as denominator)

as denominator)

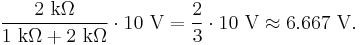

As an example, assume

,

,  ,

,  , and

, and

Since the load resistance is large compared to the other resistances, the output voltage  will be approximately:

will be approximately:

Due to the load resistance, however, it will actually be slightly lower: ≈ 6.623 V.

One of the advantages of the potential divider compared to a variable resistor in series with the source is that, while variable resistors have a maximum resistance where some current will always flow, dividers are able to vary the output voltage from maximum ( ) to ground (zero volts) as the wiper moves from one end of the potentiometer to the other. There is, however, always a small amount of contact resistance.

) to ground (zero volts) as the wiper moves from one end of the potentiometer to the other. There is, however, always a small amount of contact resistance.

In addition, the load resistance is often not known and therefore simply placing a variable resistor in series with the load could have a negligible effect or an excessive effect, depending on the load.

Early patents

- US patent 131,334, Thomas Edison, "Coiled resistance wire rheostat", issued 1872-9-17

- Mary Hallock-Greenewalt invented a type of nonlinear rheostat for use in her visual-music instrument, the Sarabet (US patent 1,357,773)

See also

References

- ^ The Authoritative Dictionary of IEEE Standards Terms (IEEE 100) (seventh edition ed.). Piscataway, New Jersey: IEEE Press. 2000. ISBN 0-7381-2601-2.

- ^ The word "rheostat" was coined by Sir Charles Wheatstone about 1845. Brian Bowers (ed.), Sir Charles Wheatstone FRS: 1802-1875, IET, 2001 ISBN 0852961030 pp.104-105

- ^ Membrane Potentiometer White Paper

External links

- .PDF edition of Carl David Todd (ed), "The Potentiometer Handbook",McGraw Hill, New York 1975 ISBN 0-07-006690-6

- Rheostat - Interactive Java Tutorial National High Magnetic Field Laboratory

- Pictures of measuring potentiometers

- Electrical calibration equipment including various measurement potentiometers

- The Secret Life of Pots - Dissecting and repairing potentiometers

- Making a rheostat

- Potentiometer calculations as voltage divider - loaded and open circuit (unloaded)

|

||||||||||||||||||||